The internet as a cultural refuge

The COVID-19 pandemic has had us encased in our domestic spaces for weeks, like nervous, unsure terminals connected to more stable terminals – computers – with social media as a substitute for our usual public social lives. Whether a natural Eden overflowing with abundance or a bin lorry spilling over with our basest passions, social media has kept us connected to official protocol, to the theatre of virtual dress codes during lockdown and to uncertainty, in equal measures. While we have been anchored in our homes, live arts have temporarily had to move to the internet. By live arts, I mean any cultural form that requires the participation of an audience, not just of artists.

#CultureFromHome has been a call to cultural resistance, a call of fluctuating intensity that has revealed people’s hunger to be with others, their yearning for all that is live, and the importance of the public space and of everything that makes us coexist with our own agency in a world open to chance, to dialogue and to processes (not always productive). All that vibrates out of shot, on the margins of screens and of codes of representation and self-representation, which can be so useful but are never self-sufficient. Though no one knows exactly what the post-COVID cultural scene will look like, we do know that social distancing and health protocols have already started to impose their conditions on small, medium and large cultural facilities. How is being prioritised over what. In this context, the digital environment offers itself – literally – as a set of windows with multiple options, as a space for creation, sharing, exhibition and cultural education on which we will have to rely, but in what conditions?

Platform capitalism and algorithmic massage

It was in the ’60s that Marshall McLuhan coined that famous phrase, ‘The medium is the message’. But in 1967, he published a book titled The Medium is the Massage, in which he argued that the media is so penetrating and so focused on our nervous system that it leaves no part of our person ‘intact, unaltered, and unmodified’, and that if social and cultural change is to occur, it will be based on knowing how the media works. This is an important endeavour. In mid-April, according to Bloomberg TV, YouTube (Google) was estimated to have grown its audience by 75% and the platform was amassing over 2 billion viewers per month. We’re talking about a mass of masses here, a mega-mass. In this situation of global house arrest, the Disney+ platform was launched in Europe, and now boasts 54 million subscribers. In late April, digital publication The Verge indicated that Netflix had 15 million new subscribers, reaching a figure of 182 million viewers and 709 million euros of profit in the first quarter of 2020. These are just some examples of what Nick Srnicek calls ‘platform capitalism’ companies, which, during the pandemic, have expanded their market share thanks to social distancing.

These online platforms manage information using algorithms and offer recommendation systems that are specific (niche) yet closely linked to the taste of the masses. The algorithms are prescriptive. The platform interfaces are dominated by the most viewed, most popular, most current videos, or those backed by the most investment from the marketing department. To return to McLuhan’s comment, you could say that platform capitalism offers us an ‘algorithmic massage’.

It is interesting that, according to YouTube statistics, 70% of what people watch is down to algorithmic recommendations. I wonder what makes us allow ourselves to be guided blindly by a machine. You could say that taste is one of the things that most obviously and generally brings together our private space and the outside. Through the things we like and hate, we come together in non-biological communities. But taste, affinities, have a private component that is not always easy to share. There are things we prefer to keep secret, things that belong to us and no one else or that can be given to a select few, private things, locked away, even though we live in a connected society with little tendency towards discretion. Maybe this is why it is easier to turn to the algorithm than to friends, because the machine doesn’t judge. It segregates us mathematically, but it doesn’t question us. And because it surprises us: now and again, it picks out a gem from the pile of digital dross and surprises us. But most of the time it doesn’t, because the algorithms on these platforms are more Catholic than the Pope, they toe the line more than the ruling classes, they spout more clichés than the mass media, and they have proven more impenetrable than any archaic institution. They are private black boxes, a secret that lives on the secrets of others and won’t be shared (sometimes not even with their programmers, if they are machine learning algorithms).

Online platforms and hegemonic languages

Following this logic of the taste of the masses for a culture of the mega-masses, language probably plays an important role. According to Internet World Stats (2019), the most commonly used languages on the internet are English, Chinese and Spanish, followed by Arabic and Portuguese, though YouTube currently features over 80 languages. In this context, which seems gloomy for Catalan, there is some good news: according to statistics regarding the rise in online audiovisual consumption during the pandemic, Filmin has seen its activity grow by 260%, more than HBO (258%), Netflix (254%), Amazon Prime Video (222%) and Movistar+ (219%). This is noteworthy because, in 2017, Filmin created FilminCAT, the first distribution platform exclusively for TV series and films in Catalan, which has gone from 1,500 products to a catalogue of 10,000 options today.

As Maria Soliña Barreiro and Judith Clares-Gavilán from the EUVOS group (Intangible Cultural Heritage For an European Programme for Subtitling in Non-Hegemonic Languages) point out in the article Public policies and strategies to foster access to films in a minority language. Catalonia and film subtitling 2015-2017 (2020), the Directorate-General for Language Policy has invested significant resources into subtitling and dubbing in Catalan since the Cinema Law of 2010, especially for FilminCAT, Movistar+, Sitges Film Festival and Cinemes Texas (Ventura Pons’s cinema). But what happens when we leave the traditional circuit, which includes cinemas, festivals and even SVOD (Subscription Video On Demand) services that specialise in independent cinema like Filmin? We are left in the hands of the big platforms.

This extreme dependence on our friend the algorithm and the Catalan language’s lack of presence in digital environments have led Arnau Rius, Clàudia Rius, Bru Esteve and Juliana Canet to create Canal Malaia on YouTube, a channel offering YouTuber content in Catalan. The aim is to compensate for the biased view of the algorithm, which is unable to make effective, community links in relation to any content that is not mainstream. The project provides a boost to the YouTube audience that consumes content by Catalan YouTubers, because it emphasises linguistic community. This way, they avoid part of the arrogant trap laid by platform capitalism companies, consisting of the use of a certain hegemonic language as part of their artillery available to reach the biggest possible audience.

Algorithmic communities vs. dialogic communities: the case of Soy Cámara

By artillery, I mean the digital tools that improve the positioning of audiovisual content and that are related to the agenda-setting (the themes covered), to the aesthetic used deriving from the popularity of an app (the Instagram filter culture, the palimpsestic, slapstick culture of TikTok), to the metadata configured, to the title chosen, to the expressions and gestures used, to the metrics of the channels themselves, to the accomplices sought to act as amplifiers... And to language. I mean using Spanish or English now and again to address the guests at the virtual banquet you want to organise, who turn you into a pseudo-impostor momentarily for the sake of targeted communication. This is the case because we have presumed that social media is a place for distributing information and the self, rather than a space for creating affection (though it can also do this, sometimes and to a certain extent). On top of this, we have accepted that there is one way of doing things and it is dictated by the algorithm, like when YouTubers had to stop making short videos because the algorithm started to prioritise longer videos, as this way, the company accumulated more viewing time and the viewers stayed on the interface for longer.

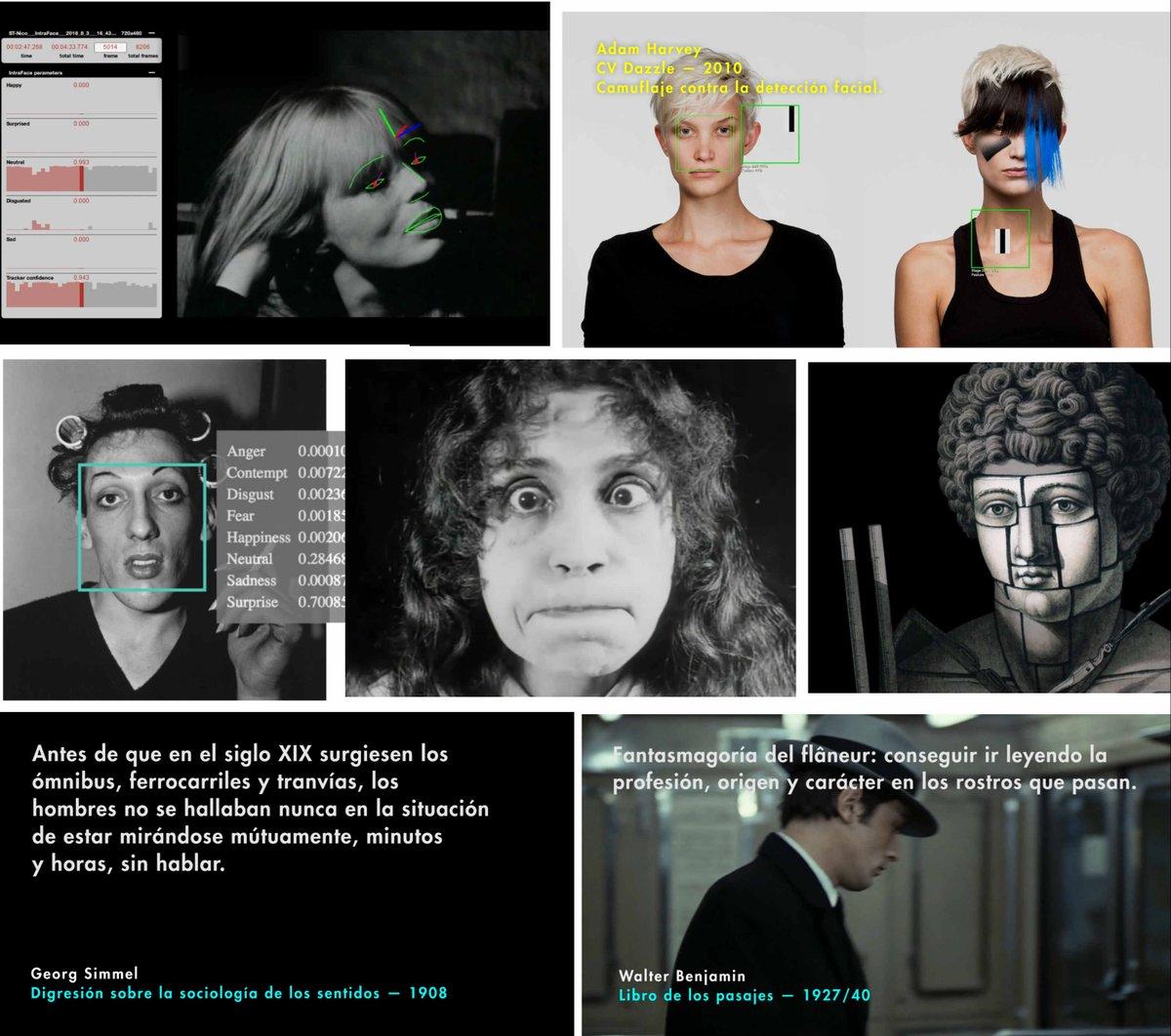

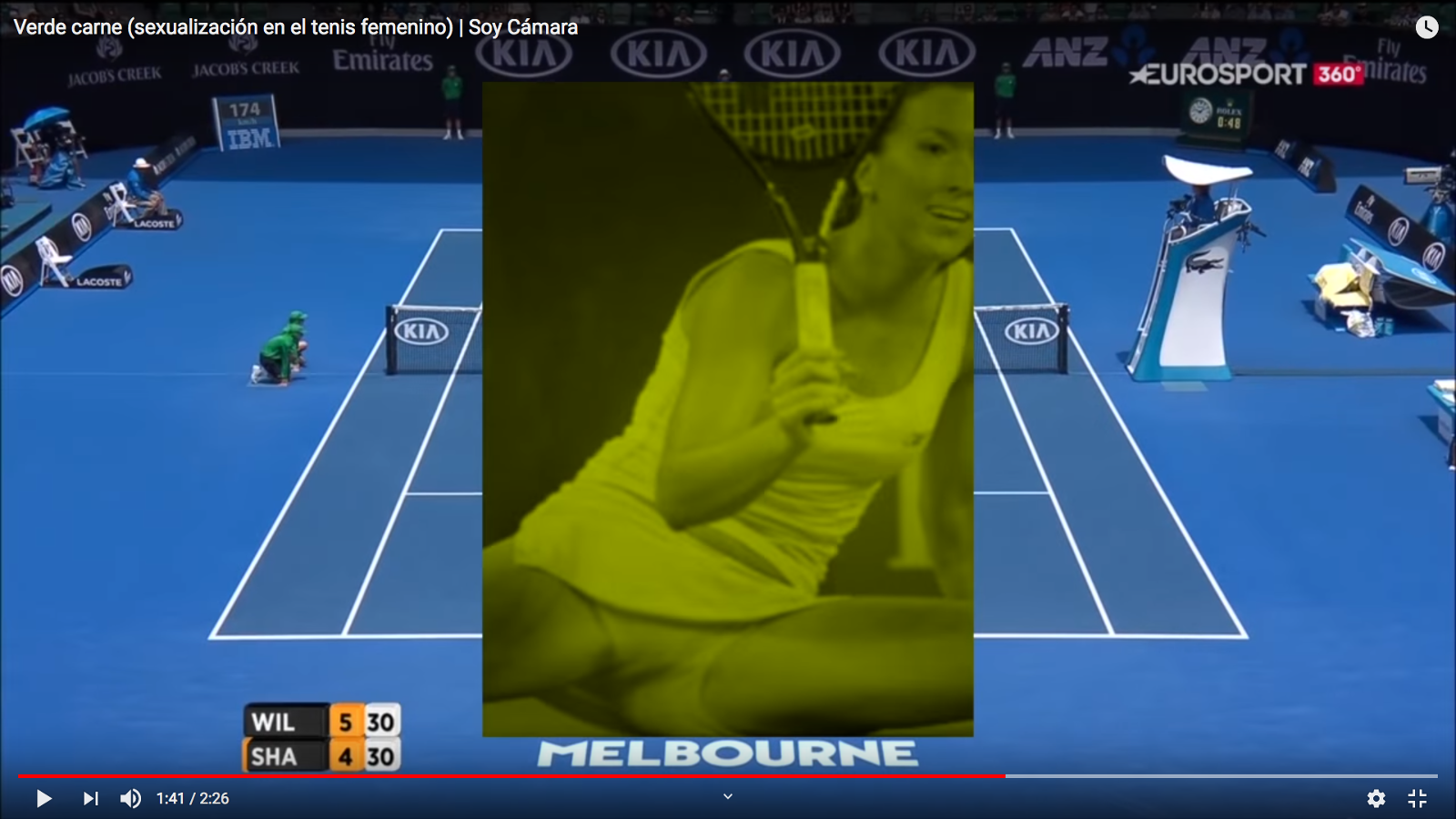

Even with a project that is far from mainstream like Soy Cámara, the essay film YouTube channel put together by the CCCB (2010–2020) and curated by Andrés Hispano, Fèlix Pérez-Hita and, in recent years, by me, we have sometimes been tempted to use striking titles as bait for audiences, under the advice of the social media department. But we have resisted, partly because we don’t want to, partly because we don’t know how to. Something strange happened with one of the programmes, which criticised the sexualisation of women’s tennis. The combination of ‘female’ and ‘sex’, along with the involvement of an online sports media outlet that embedded the content on its website, took the piece to a large audience that, obviously, didn’t watch any other content on the channel and enjoyed the video not as a critique, but as a collection of tennis players’ knickers and cleavages. The algorithm diversifies audiences, but in unexpected directions that may even cancel out the meaning of your content without need for any memetic intervention on it, all thanks to the (sometimes dark) magic of our friend the algorithm.

The algorithm will never catapult us to huge numbers because we don’t want to pay the price of the algorithm. Because even if we did pay it, we don’t make content for large audiences, nor do we know how to, because we want to concentrate more on what we are saying and less on the potential recipients (there was a time when cultural institutions were obsessed with reaching many different audiences). ‘We’re talking to anyone, not everyone’ is one of the running jokes within the project, a serious joke that expresses that the audience does not set the perimeter of our project. Instead, our audiovisual content (in Catalan, Spanish and English, depending on the language of the person speaking) is like a recitation out loud that anyone can catch from between the digital cables, even those who have come to see tennis players’ knickers. A dialogic (dialogue-orientated) community is not the same as an algorithmic community. The difference lies in the type of connection made.

This reminds me of what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu said about television:

‘With television, we are dealing with an instrument that offers, theoretically, the possibility of reaching everybody. This brings up a number of questions. Is what I have to say meant to reach everybody? Am I ready to make what I say understandable by everybody? Is it worth being understood by everybody? You can go even further: should it be understood by everybody?’

Should my online discourse be understood by everybody? Should I force my discourse into a shape that is suitable for this global audience? Definitely not. This would equate to losing a linguistic community, a community of meaning and the possibility of dialogue itself.