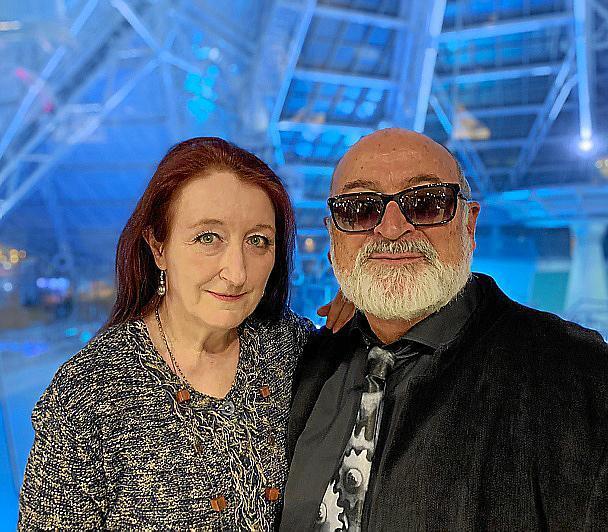

French translator Annie Bats has resided in Barcelona since the 1980s. She came with a view to becoming more proficient in the Catalan language and, spellbound by the city, she ended up staying. For some time now, for family reasons, she has lived between Catalonia and France. She happened to be in a village on the border between Limousin and Périgord when the lockdown triggered by the Covid-19 health crisis began. The idea of skipping milestones, once again, has always appealed to her. “These days I am living like an exile in my own home, but with everything going on in Catalonia I feel really involved,” she remarks in our conversation via Skype. Last December she received the Ramon Llull Award for Literary Translation, granted by the Fundació Ramon Llull and endowed with 4,000 euros, for her adaptation into French of Llefre de tu (Ogre de toi), by Biel Mesquida (Club Editor, 2012).

How did you come to translate Llefre de tu and how did you tackle it?

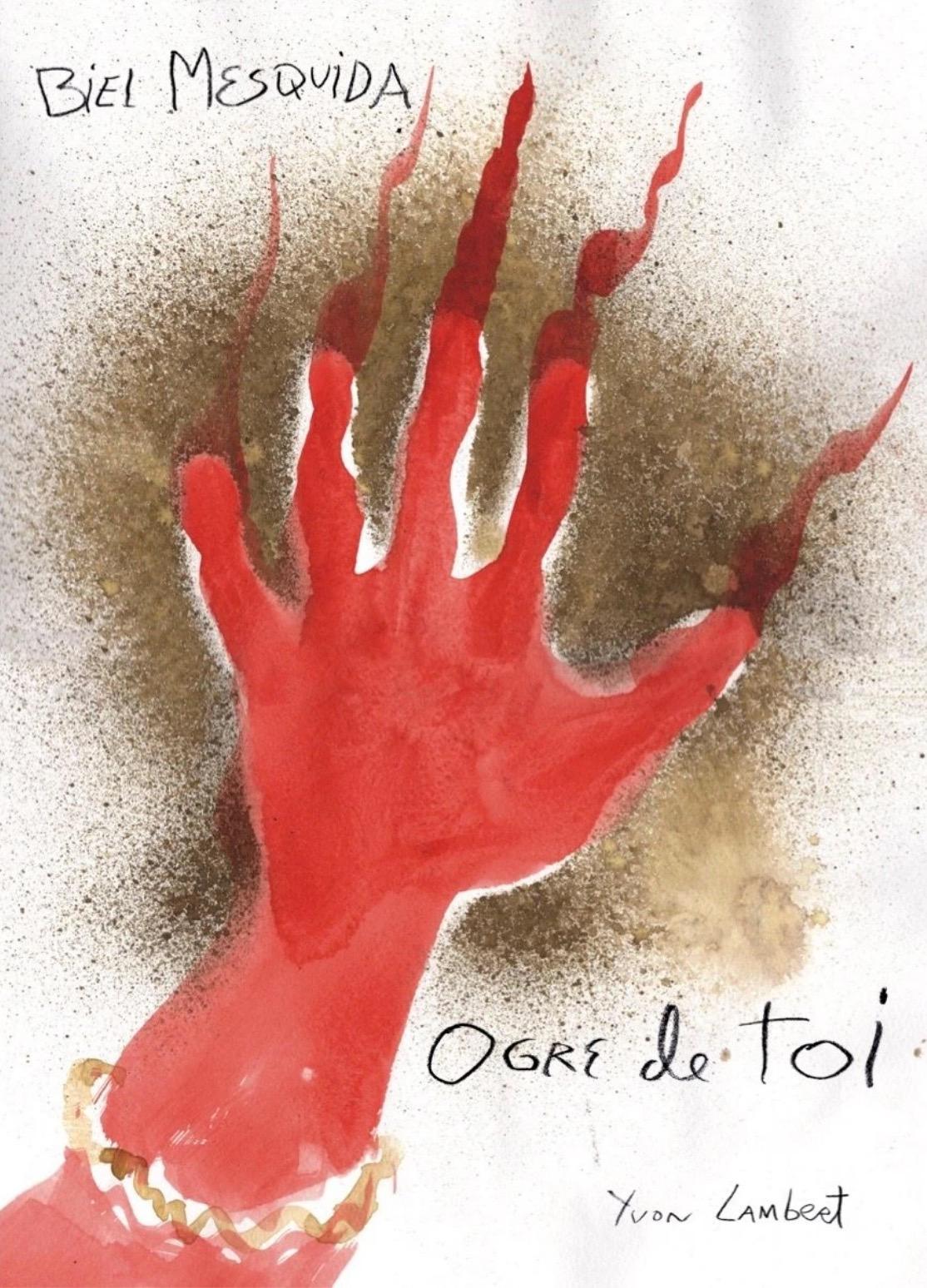

Actually, this book was commissioned by Maria Bohigas and Biel, whom I have known for many years, so it was a three-way collaboration from the very beginning. Biel was thrilled that this book would be translated into French, because he felt it was the most French of his books. And he really believed it was the book’s destiny to be translated in France. I translated a few sample pages to seek out publishers until Biel found one, Yvon Lambert, who was a gallery owner and essentially publishes art. He was very interested in the project. Then I proceeded to do the whole translation, always in contact with Biel [the volume was published last year, with a foreword by Mathias Énard and a cover by Miquel Barceló]. It’s a commission, if you wish, but it’s a natural commission, on account of my friendship with Biel and the sort of text it is, which piqued my interest.

When translating, you say that you “scoured” the Diccionari Alcover-Moll and that contact with the author proved primordial.

The Diccionari Alcover-Moll was a wholly essential tool. We already know that Biel makes full use of the Mallorcan language, but it must be said that this difficulty is only a fraction of the work. The rest entails a great deal of reading, which is not limited to the lexicon. And Biel helped me out with this task. He answered my questions, we had conversations, and he shed light on difficult passages for me. Being able to work in close conjunction with the author is a privilege for a translator. It’s a very different reading dynamic. It’s a text that has had critical readings but it’s still a new text. I have occasionally come across more classic texts on which there were studies whose consultation was absolutely necessary, but this is somehow a virgin text.

Once you had rolled up your sleeves to set about the translation, what specific difficulties did you run into?

The specific difficulty is the one that applies to any sort of poetic text. There are poems and prose in Biel’s book... And the prose itself is rhythmic. Biel employs lots of puns, word play,neologisms, and so on, which ought to be preserved. Besides that, this book makes a great deal of reference to French literature. It features passages in French highlighted in italics and this strangeness, this hybridisation, is erased in the translation. What’s more, the text also includes quotations from French authors here and there, concealed beneath the Catalan, and that must be identified. So painstaking attention was afforded to this background, which is like a kind of archaeology of the French references in the text. The target text, in French, cannot be equivalent to the Catalan text, because this very association with French is inscribed in the Catalan text. Now it’s another association. A downright Gallicisation... In any case, it’s a text that plays enormously with all hybridisations. Biel sort of interweaves the quotations, not only the ones in French, but also different languages, the language of science, art, etc.

What would you say is the most surprising thing about this book?

I wouldn’t talk about surprise, it’s more inspiring than surprising... I think it’s this kind of steady crossover from one register to another, from lyrical to sarcastic, from one lexicon to another, from poem to prose, although all the prose therein is poetic. And also the figure of Aràlia, the great absentee who is the one who “inspires you to write”, or the figure of the “Recordador” (‘Rememberer’), who is the one who remembers, obviously, the great absentee and, at the same time, the one who preserves and triggers the memory of literature and of languages.

How did you make Biel Mesquida’s acquaintance?

I read Biel’s work before I met him, when I was studying Catalan. I studied Catalan while pursuing Modern Languages at university. I had to choose a living language and I picked Catalan after a trip to Barcelona, when I found out it was an option. It was a bit of a coincidence.

But why did he catch your eye?

I have had a Jacobin education. However, this was offset by having Breton, Basque and Occitan roots in my family. And a significant point is my reading of the troubadours, the creators of some of the great Western poetry. They devised, they wrote in the “vulgar language”... And their language is half lost. And just when I arrived in Catalonia I heard a living language that resembled it. When I started studying Catalan I often travelled to Barcelona and bought books, both classics and non-classics. And at one point I thought I’d do my dissertation on the translation of the Foix sonnets entitled Sol i de dol. I translated them all, for myself; they weren’t published anywhere. I didn’t finish my dissertation because I didn’t care much about academia. That was the ‘80s.

And how did you end up befriending Biel Mesquida?

Through Arnau Pons, who introduced me to him. Around 1995. We shared a common passion for language, for poetry... The first book of his I read was L’adolescent de sal, when I was learning Catalan. And that’s the first thing I said to him.

What else acted as a gateway to Catalan literature for you?

The love of foreign languages. I’ve always been attracted to languages, all human speech, singing. Listening to songs in every language is something I’ve always done. I was born in Morocco, to French parents, and then my parents returned to France. We arrived in Paris, in the Belleville neighbourhood, when I was four years old. It was a neighbourhood of artisans and with many successive waves of immigration. Armenians, Russian Jews, Polish Jews, Spanish Republicans... It was a working-class neighbourhood. They say it hosted the final barricade of the Paris Commune in 1871. My childhood was marked by hearing foreign names, hearing different languages, and talking to people who had very different stories. I’ve always felt like I live between borders, crossing borders. Every home had stories of the world. They were stories of forced exiles. The history of Europe and of colonialist France too. And I suppose I ended up settling on Catalan because I fell in love with Barcelona, with hearing this language that resembles Occitan in such a beautiful city. When I got there it was still working-class too. That has changed a lot. But I think that what brought to me there was that connection between the voices of the world and this memory of the language of the troubadours. La rosa de foc (The Rose of Fire) and La flor inversa (The Inverted Flower).

You have mostly translated poetry from Catalan to French, haven’t you?

Yes, lots of poetry. Maria-Mercè Marçal, Arnau Pons, Víctor Sunyol, Víctor Obiols, Segimon Serrallonga, to name but a few. I have also translated into Catalan. Ramon Lladó and I translated Perec, Queneau and Roussel. I like shared reading, with someone close to you or with scholars, which is also a kind of relationship. For instance, Ramon Lladó and I were fortunate to have access to many studies when translating La Vie mode d’emploi (Life: A User’s Manual) by Georges Perec. And that helped us delve further into the structure of the text, which is very complex. Swinging from one language to another allows me to better understand the writing process.

When it comes to translating a text, what steps do you always try to take? How do you understand the idea of translation?

There’s the part that involves meticulous reading, at the level of the words of the text, and the text as a whole. Understanding the work you are translating as well as its entire architecture and all its constituent parts. It’s a task that involves understanding its unique mechanisms, its rhythm... The translation of poetry is sometimes considered in a very restricted manner. For example, the translation of Shakespeare into Catalan: there are people who fight for the metric standard and it all ends there. Sometimes I’m surprised by these reductions. There are blurred issues. Reducing translations to philological issues strikes me as being very narrow. It’s a matter of poetry.

The act of choosing these authors to translate and your predilection for poetry speaks of your perspective on literature and your own universe...

It’s when the possibility of translating is most clearly raised. I think everything is translatable, although we could qualify that later. I understand translating as rewriting. For there to be rewriting, the text you translate must be a text that is creative. Literature is not communication; it is creation. As Deleuze said, it is resistance. Texts that resist in every respect, like an artistic statement, and that also resist easy interpretation.

Looking at the writers and texts you have translated, I suppose that tackling resistance is also part of the very challenge of translating, it’s like climbing a mountain that...

It’s like climbing a mountain that... is worth it. It’s a challenge for you but it’s also a reflection on the circulation of texts, of books.

You’ve also taken part in numerous recitals…

I like orality, the voice. There are people who think that poetry should only be read in print and not read aloud. I believe that there is a poetic tradition that allows and seeks recital, to be voiced. Biel is a person who reads aloud magnificently. His timbre, diction, vocal melody... He is someone who reads and sings really well, especially the French repertoire.

What interests you about the Catalan poetry scene?

I don’t have a bird’s-eye view of it. Yes, I can say that Catalan poetry is very active, it resists. I’ve often been to L’Horiginal to hear the poets, rather powerful people, but I couldn’t paint a picture of the scene. But it’s a cultural tradition in which the oral tradition is very much alive. Look, right now, I feel like translating Blanca Llum Vidal.