Academic and literary institutions read texts conditioned by the space they occupy within cultural hegemony, thus revealing the unequal distribution of literature that favours an opposition between ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’. But so-called ‘marginal’ literatures, and their ‘edgy’ writers, are fully aware of their position on the periphery, which they can use to subvert ideologies and hierarchies characteristic of the industrialisation of the book and canonical literary practices, and, at the same time, to take advantage of the centre. In turn, the centre can use these peripheral literatures; it can imitate their forms or assimilate them, disneyfying precisely all the things that made them marginal, so that it does not offend any established moral value, even though it sometimes seems to.

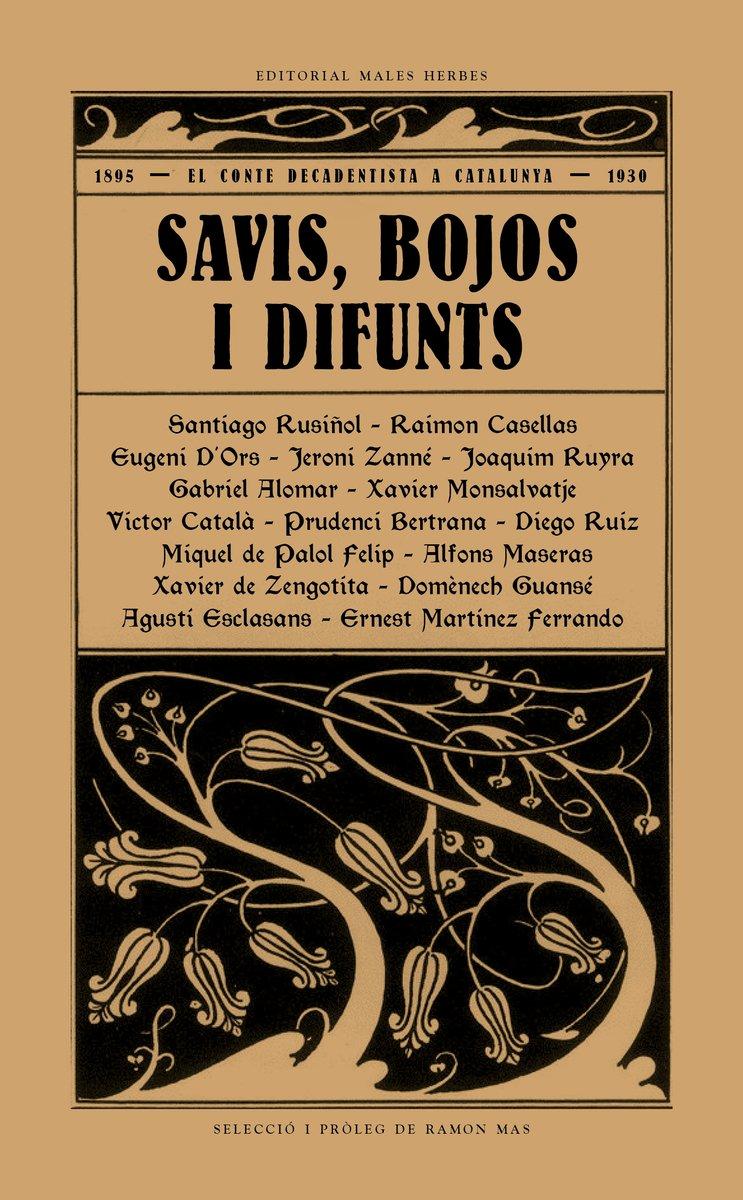

This is nothing new: experts have been mulling over the subject for years, comparing, classifying, defining this and other issues, like the recurring idea that there is a lack of counter-canonic tradition in Catalan fiction. While poetry was the artistic form par excellence in Catalonia during the Renaixença, the Modernist period and Noucentisme, fiction was made up of various traditions that moved on the dark side of the moon. Figures like Rafel Nogueras Oller and Juli Vallmitjana, for example, portrayed marginalised social realities that were uncomfortable for the bourgeoisie at the time. Francesc Trabal, Carles Sindreu and Ramon Vinyes, meanwhile, struck up intimate dialogues with the European avant-garde movements. And finally, Agustí Esclasans, Caterina Albert et al. looked to the French Decadent movement to narrate forgotten underworlds, as Ramón Maria del Valle-Inclán and others would do on the rest of the Iberian Peninsula. Recently, some publishing houses have taken to rescuing these forgotten trends, like in the case of the volume Savis, bojos i difunts (‘Wise, Mad and Deceased’, Males Herbes, 2018), with its unmissable introduction by Ramon Mas.

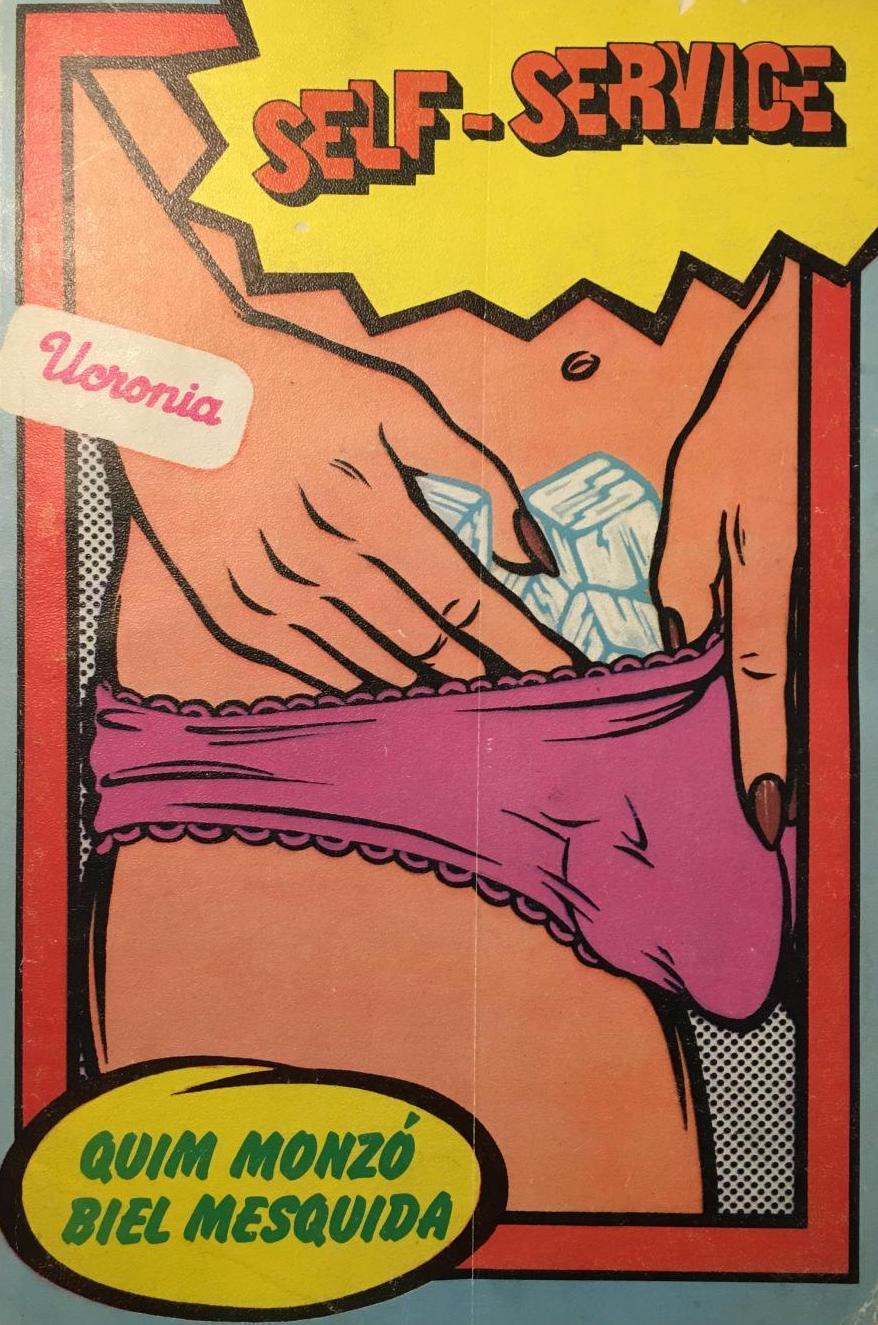

Even with Francoist censorship still alive and kicking, and after a long period of Catalan publishing being little more than symbolic, the novel picked up almost Olympian momentum. As well as the boom of feminist writers who used the novel as a tool to transform society in the seventies, a new type of fiction emerged: one that was influenced by French post-structuralism, by Guy Debord’s situationism, by the Nouveau Roman of Robbe-Grillet or Marguerite Duras and by the North American underground scene of the beatniks and pop art. A fiction that presented technical debates, experimental obsessions and literary ambition that are rare today.

And so, Jordi Sarsanedas, Manuel de Pedrolo, Guillem Viladot, Amadeu Fabregat, Terenci Moix, Biel Mesquida, Blai Bonet, Isa Tròlec, Quim Monzó, Joaquim Soler and Antoni Munné-Jordà began to make a type of fiction understood as an autonomous task and located on the margins of official culture. Their common thread continued through the work of Boro Miralles, Ventura Ametller, Miquel de Palol and Francesc Bononad, in contrast to a literature protected by historicist critique, which prioritised social realism for political reasons, as a paradigm of resistance against a long, now-dying dictatorship. Some authors soon had to decide either to write for a small yet loyal minority or to be assimilated by the centre and perhaps (perhaps!) be able to live off their writing, in exchange for publishing domesticated artefacts for the general public.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the so-called postmodern literature of William Gaddis, Thomas Pynchon, Donald Barthelme and John Barth would influence generations of writers, up until at least David F. Wallace. These writers, in turn, dialogued with neobaroque authors Lezama Lima, Severo Sarduy and Cabrera Infante, as well as the Argentinians Bioy Casares, Borges, Cortázar, José Donoso and Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes, who would also influence their own respective fictions. And meanwhile (how many ‘meanwhiles’ will we need?), here, this necessary extraterritorial dialogue between various local or international trends seemed to be forgotten, resulting in shipwreck-style isolation from any hint of tradition. The outcome is a kind of ‘selfie literature’, where the author matters more than the quality of the work itself, within a literary system that reproduces the same inequality politics that exist at the heart of neoliberal capitalism and industrial society.

CODA: Today, the rise of new publishers and new voices that connect with these different literary trends or subgenres (because we need to be aware of different traditions, both close to home and further afield, to be able to break with them) offers fertile ground for planting the seeds of a more egalitarian literary permaculture. A permaculture that does not depend exclusively on commercial success, on writers’ hunger for fame or on awards and endorsements, instead revealing more heterogeneous ways of narrating (standardisation does not tolerate difference, so it becomes censorship), of thinking about the Other to understand ourselves a bit better, and offering the possibility to imagine worlds beyond the end of our noses. Ultimately, our literature will germinate universally when it is aware of its own polysystemic diversity and can unselfconsciously establish dialogues with other literatures, from here to Timbuktu.

Many thanks to Borja Bagunyà, Joan Todó, Francesco Ardolino and Ramon Mas for their suggestions when I was preparing this article-bonsai.