‘It was so long ago now that I stepped off the boat in New York!’, Rafael Guastavino thinks to himself as he stands in the middle of the platform admiring his latest creation, the City Hall Loop, the main station on the city’s first subway line, on its much-anticipated inauguration day: 27 Octo-ber 1904. A few minutes earlier, the city’s mayor, George McClellan, finished off his speech with the slogan: ‘City Hall to Harlem in fifteen minutes!’ The journalists and authorities present seem surprised by the design of the terminal, which is meant to be one of the cornerstones of the New York subway system. Guastavino watches them and smiles. He knows it is different to the other stations on the line built up until now. It is a space designed to win over travellers reluctant to use such a modern mode of transport. A miniature architectural gem that brings together all the ingredi-ents that make up his signature style: polychrome tiles, elaborate windows and Catalan or timbrel vaults. This latter element is his modernised version of a vault used commonly in the western Medi-terranean region for centuries. The Guastavino Tile Arch System has brought him much success since he patented it in 1885.

Right now, no passer-by could ever imagine that under City Hall, at the intersection of Center Street and Chambers Street, there is a kind of ‘underground cathedral’. It is a unique, unusually elegant construction composed of a daring sequence of segmental vaults with lunettes separated by transverse ribs which adapts perfectly to a complex stretch of track: a very pronounced bend. He is proud of the result. Everyone congratulates him: on the magnificent glazed skylights that filter through the natural light, tinting it slightly blue, and generate a serene, relaxing atmosphere, despite the depth; on the careful selection of colours for the fifty thousand glazed rectangular tiles arranged in a herringbone pattern on the vaults; on the beauty of the brass and iron lamps hanging from the ceiling; and on the space’s overall feeling of weightlessness.

A sense of total calm reigns when, after the institutional ceremony, he finds himself alone on the platform. The absolute silence that envelopes him brings to mind all the time that has passed since he set foot on American soil. ‘Twenty-three years! Twenty-three years have gone by since I left Barcelona and arrived in New York’, he whispers, and, for a moment, he shifts his gaze from the ceiling and contemplates the subway tracks, which get lost in the tunnel’s dense darkness. His ori-gins are far, far away. They are in Valencia, the city in which he was born in 1842.

A series of blur-ry images from long ago pass through his mind in quick succession, starting with his father’s car-pentry workshop, hardly a hundred yards from the Baroque door to the city’s cathedral and a stone’s throw from the Llotja de la Seda. Then, the faces of some of his classmates from his little school on Carrer Ample de l’Argenteria, followed by his move to Barcelona to study at the School of Master Builders. The warm welcome given to him by his uncle and his wife, a couple with a suc-cessful textile company and an adopted daughter, Pilar, who he would leave pregnant not long after moving there. The wedding he didn’t want, the birth of his four children, his constant cheating. The memories keep coming: his participation in important architectural projects, like the Batlló factory and the La Massa theatre in Vilassar de Dalt, brought about by his uncle’s connections to the Cata-lan bourgeoisie; hiring his lover, Paulina Roig, as a governess for his favourite and youngest son, Rafael, and the scandal it caused; the divorce and his downward social and economic spiral. Finally, his bid to escape and start a new life in the United States; the fraudulent pyramid scheme with false promissory notes he organised to fund his trip; his wife and his older children’s move to Argentina (he would never see them again); stepping off the boat in New York at the age of thirty-nine, with-out knowing a single word of English and with a few thousand ill-gotten dollars in his pocket; pass-ing through the Immigrant Registration Office on Ellis Island with his new family: his son Rafael, Paulina and her two daughters; his first job as a draughtsman for an architecture magazine... All in all, a complex story that, strangely enough, put him in the right place at the right time.

This unrepentant and spendthrift – and daring, intuitive visionary – wasted no time in making the most of US society’s fear of big urban fires. Incidents like the blazes that devastated Chicago and Boston between 1871 and 1872 called the safety of buildings with wooden structures into question. Authorities and architects alike were desperately looking for new building techniques based on the use of fireproof materials, and he had the perfect solution: the Catalan or timbrel vault, a fire-resistant covering he had used in various public and private buildings in Barcelona and the surrounding area.

Guastavino ambles towards the stairs to exit the subway and smiles when he recalls the peculiar publicity stunt he thought up to showcase his product. An unexpected spectacle in which he utilised a deeply rooted Valencian tradition. A convincing, effective way of demonstrating that his ‘weapon’ against fire worked. All he had to do was build a couple of small test buildings with Cata-lan vaults, invite the press and, without warning, set the place on fire. He would never forget the stunned expression on the attendees’ faces as they watched the ceilings withstand temperatures of over a thousand degrees Celsius without collapsing. This flawless marketing campaign quickly caught the attention of Charles Follen McKim, one of the period’s most outstanding architects, who tasked him with building Boston Public Library. The project’s spectacular results soon made him the favourite builder of all the architects in vogue at the time, such as Richard Morris Hunt and Cass Gilbert. His method allowed them to adapt all the monumental grandeur of churches and cathedrals to public buildings and was the perfect fit for the elegant, sober beauty of Gothic and Renaissance Revival style.

Guastavino slowly ascends the subway steps and observes the reddish ceramic pieces that make up the floor. Like the polychrome tiles on the vaults, they come from the factory he set up in Wo-burn, Massachusetts, in 1890, shortly after creating the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Compa-ny. This was the company that made him rich and would be passed on to his son Rafael, now that he had decided to retire.

Before reaching the surface, he stops for a few seconds; he fears the hubbub of Manhattan might lead him away from his train of thought. He knows the key to success lies in something seemingly simple: the adaptation of the centuries-old Catalan vault building system to modern, monumental buildings. A quick, fireproof system that is also cheap, as it requires no centring or formwork. Each layer of tiles is supported by the layer beneath, which allows for the construction of vaults and domes between ten and twenty centimetres thick and up to forty metres wide. Guastavino learned this traditional technique from his forebearers and improved it, by using Portland cement instead of gypsum.

This series of ingredients combined with his knack for detecting business opportunities made him the most prestigious master builder in the USA. ‘It all happened so fast! Guastavino fever spread like wildfire!’, he thinks, with a mixture of pride and melancholy. Over the last sixteen years, the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company has installed ceilings in a host of buildings, including the lobby of Carnegie Hall in New York, the Spanish Pavilion at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, the mansion belonging to magnate George W. Vanderbilt II, the Universities of Vir-ginia and New York, Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, the Bank of Montreal, Minnesota State Capitol, Madison Square Presbyterian Church, Rodef Sholem Synagogue in Pittsburgh and the Smithsonian Museum in Washington.

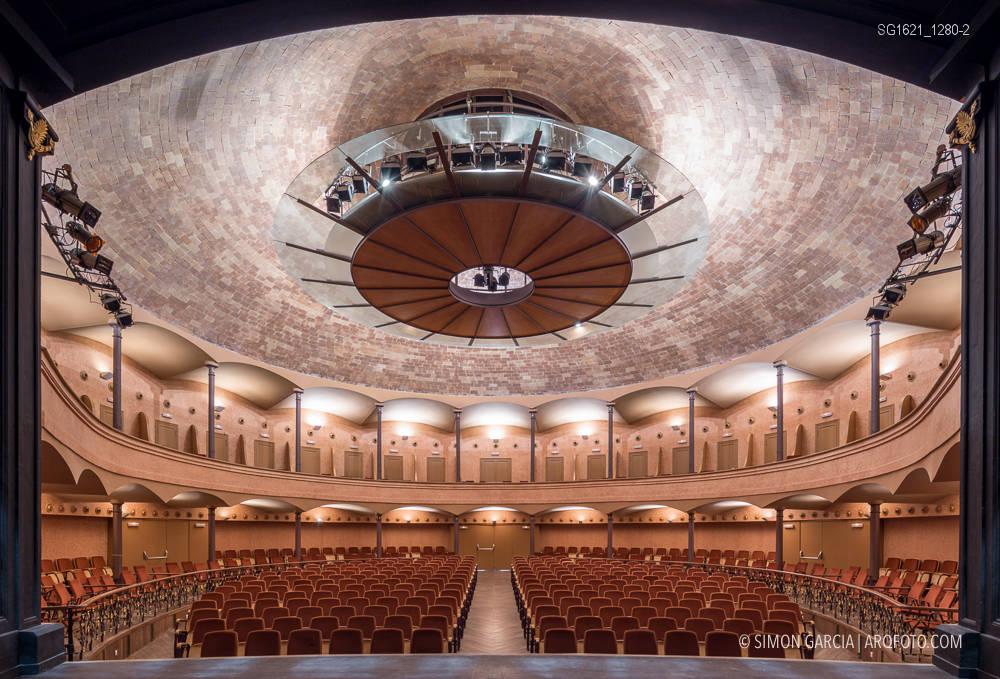

Once outside, he smokes a cigarette in front of the City Hall that welcomed him, along with thousands of other immigrants who, like him, came in search of the American Dream. He’s finding it harder and harder to leave Rhododendron, his majestic residence surrounded by vineyards in Asheville, North Carolina. That's why, at the age of sixty-two, he has decided to pass the business on to his son Rafael, who has been learning the trade with him since he was a teenager. He trusts him implicitly. A few days ago, he supervised the work being carried out by the company under Queensboro Bridge, which connects Manhattan and Queens. This is one of his latest projects, which involves palm-shaped structures that evoke those of the Llotja de la Seda in Valencia. Lately, he’s been feeling a strange emotion: a kind of tender longing for the places where he spent his childhood and youth. He was unable to finish the vault – with a span of seventeen metres, a rise of three and a half, and a four-metre-wide oculus – for the ceiling of the theatre in Vilassar de Dalt. When it was opened, on 13 March 1881, he had already boarded the ship for New York at the port of Marseille.

Nonetheless, he still has some professional contacts in Barcelona. Barely three years ago, he advised businessman Eusebi Güell on the design of the vault for the Asland Cement factory in Castellar de n’Hugh, in the county of Berguedà. Thanks to these business connections, he stays informed of the urban planning and architectural changes taking place in the city where he studied to be a master builder, despite the distance.All he has left of Valencia, though, are faded, discoloured images, like old photographs. But still, now and again, the memories become so intense that, just for a second, he can breathe in the salty seaside aroma of Malva-Rosa Beach, the smell of chalk dust that filled his school on Carrer Ample de l’Argenteria, the resinous fragrance that pervaded his father’s carpentry workshop. These recol-lections manifest powerfully every time he thinks about the Basilica of Saint Lawrence, an ambi-tious project he wants to offer the city of Asheville in exchange for being buried in its crypt.

The night swathes Manhattan, and before heading back to his hotel, Rafael Guastavino stubs out his cigarette and takes a final look at the entrance to City Hall Loop station. As soon as he arrives at Rhododendron, he will sketch the final design for the façade and floor plan of the church where he wishes to rest forever: a building inspired by Valencia’s Basilica of Our Lady of the Forsaken. This thought immediately sets off his olfactory memory again: through the sickly-sweet whiff of incense and hot wax that permeated the church, he distinguishes the fresh scent of the orange blossom es-sence his mother used as perfume on Sundays.