Until the world ends, no one can confidently identify the connections between all the events that took place in it. So, today, I can believe, without fear of being wrong or a desire to be right, that if Ramon Llull hadn’t invented the compass rose, I would never have set off to navigate the world. If I hadn’t travelled so many hours, gazing at the horizon and the possible directions available to me, perhaps I wouldn’t have decided to cross borders and head off to unknown lands, as the Mallorcan sage did in his time.

Llull was driven by the desire to spread his knowledge, of which he was sure. I, meanwhile, have little knowledge and am sure of none of it. My travels have been guided by curiosity for the knowledge of others. In any event, the great teacher Llull left contemplation behind and took action, convinced the world needed the common denominator of a certain faith. I left behind my fledgling contemplation with the feeling that it would be more honourable to set off and observe the possibility of a common denominator that, shut away in my reflections, I could only sense.

We are all students of those who came before us, and if our conception of time is circular, those teachers of ours will also be our students.

I had decided to travel around the planet for approximately two years, though the circumstances led my restless spirit to become a nomad. It is from this nomadic position that I am writing these words.

I set off in early June 2018. Westward. My first destination was as much an idea as it was a place: revolution in Cuba. And, from there, onto Panama. Then Colombia, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Easter Island, Polynesia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Japan, China, Malaysia, Singapore. The end point for this journey around the world was another idea, but this time the opposite of revolution: the United States.

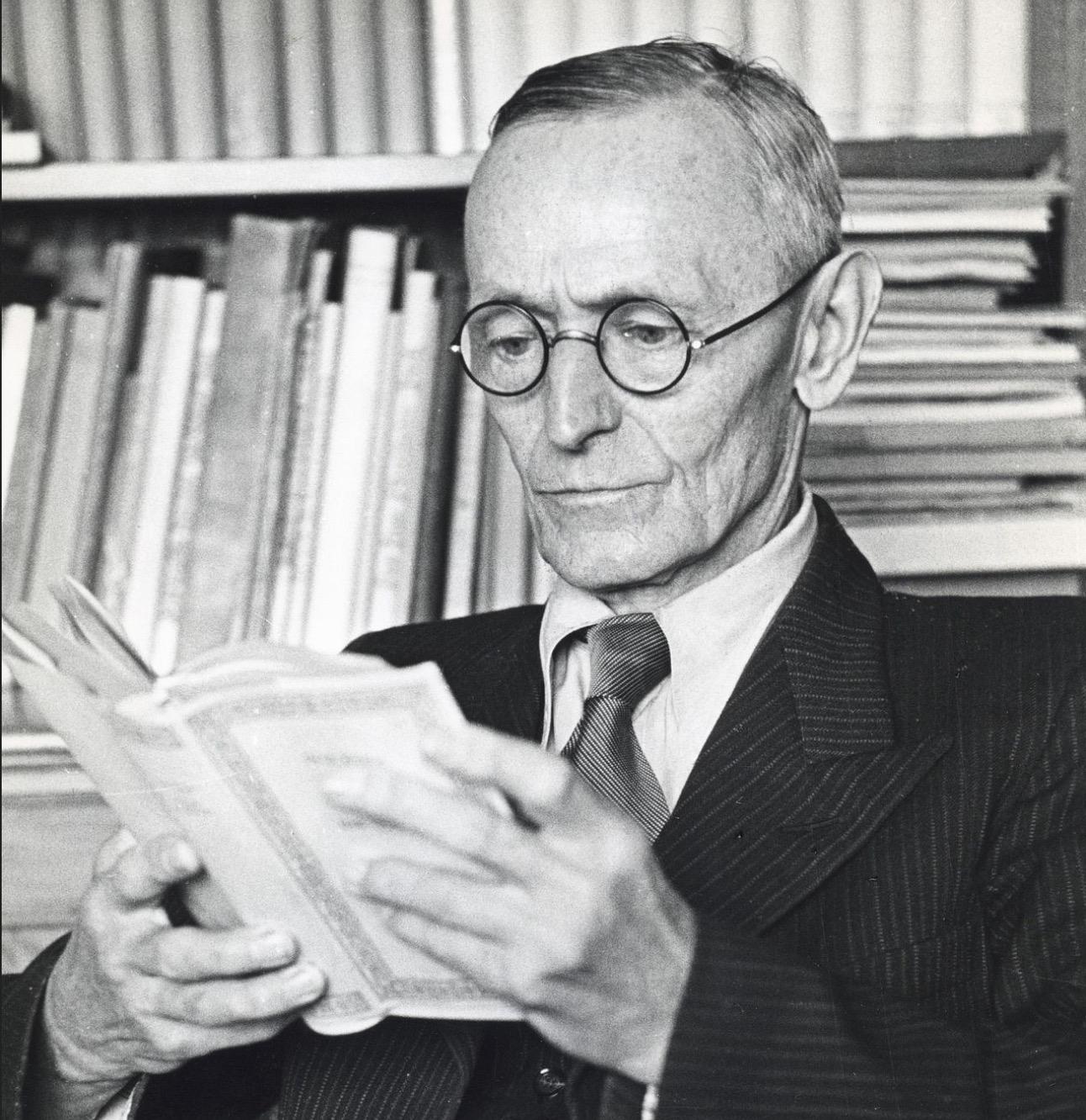

Leaving contemplation behind and taking action was part of my motivation. So was the certainty that the world was not just what I and those around me thought it was. I am reminded of some extracts from Hermann Hesse’s book, set in the twenty-fifth or twenty-sixth century, The Glass Bead Game, in which the main character Josef Knecht, an inhabitant of the wealthy province of Castalia, declares,

‘I do not want to go out into the world with insurance in my pocket, in case I am disappointed. I don’t want to be a prudent traveller taking a bit of a look at the world. On the contrary, I crave risk, difficulty, and danger; I am hungry for reality, for tasks and deeds, and also for deprivations and suffering’. Then: ‘(...) I had made the discovery that I was not only a Castalian, but also a man; that the world, the whole world, concerned me and exerted certain claims upon me. (...) the world and its life was in fact infinitely vaster and richer than the notions a Castalian has of it’.

Some, when they found out about my plans, warned me it wasn’t safe, that anything could happen to me. Anything can happen anywhere, any time, I replied. What is safety, if not the other side of the coin from fear? ‘Kill fear with love, not love with fear’, wrote Llull.

I didn’t know what I would find. Not just outside: inside, too. I didn’t know whether or not I would feel strange, want or need to go home, suffer from impatience or loneliness. Whether I would be happy or sad. Whether I would act wisely or foolishly.

Not knowing where you’ll sleep that night makes the day feel complete. Not knowing what you’ll eat. Not foreseeing the people you’ll speak to, who will help you or who you’ll help. Chatting away in other languages to tell people about where you’re from and to ask about the new place you’ve found yourself in; to talk about the first culture you came into contact with, about the people who surrounded you at the beginning of your life; and to understand the beliefs and feelings of those who are accompanying you now.

Slowly but surely, you start to enjoy the chain you’re a part of. You start to understand that you have to connect with the link next to you to become strong. You start to see that all the links in the chain have the same feelings and fears and ambitions and hopes. You start to see that, if they don’t seem strange to you, you’re not strange to them. Bit by bit, the whole world becomes your home. There’s always something to eat and somewhere to sleep. Someone who gives you work, a smile, a hug, a day spent among friends or family. You see that, actually, there’s no such thing as strangers. That, if you are, everyone else has no choice but to be. Because, faced with what is, we are. Whether it’s a tree, a lake, an animal.

You see that we all have many more similarities than differences, reasons to get closer than reasons to move apart. That what really matters is whoever is at your side. That you matter to whoever has you at their side. That identity is not what differentiates, but what brings together. That the only thing that divides is identification. That, to know who you are, you don’t need to know who others are. You just need to know that they are.

You see that the world is not the idea we have of it. The world is a little house where a miracle would have to happen for those who shout the loudest to listen to those who can’t seem to make themselves heard, where all those who have more than necessary are and all those who are have what is necessary.

Let’s go back to Hermann Hesse and the words of his protagonist:

‘My teacher Jacobus had kindled in me a love for this world which was forever growing and seeking nourishment. But in Castalia there was nothing to nourish it. Here we were outside of the world; we ourselves were a small, perfect world, but one no longer changing, no longer growing’.

It’s not hard to see our planet as Castalia and know that, if we left it and found other beings, we would at least share the radical experience of being trapped in the same, incomprehensible universe.